Inflation, Deflation & Reflation

Which way are we headed?

Year 2009 will long be remembered as a tumultuous one. Asian markets fell and then bounced back with equal vigor. HSBC’s Asian Economics notes that “the rebound, in part, reflects the deft policy response by both central banks and treasuries, with rate cuts and spending boosts coming hard and fast once the data started to wobble.

Over the past year, the region’s governments have implemented some of the worlds’ biggest fiscal stimulus programs, while cutting policy rates with equal panache.”1

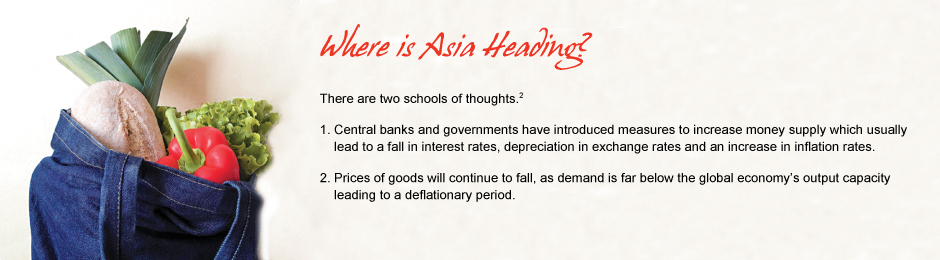

The monetary policies, put in place after the global financial crisis, could be deemed inflationary. But there is debate that with output running at well below capacity, inflation is unlikely and deflation will most possibly rear its ugly head.

Inflation Is Well And Alive

However, a closer look at the Asian markets show that inflation is the more likely scenario for Asia ex Japan. Notably, consumer price indices have started to peak again and firms are reporting rising output prices.1 Inflation pressures may not necessarily explode immediately but over the course of the year, central banks in Asia may have to face the question of how and when to reel back on their pump-priming measures.

“Inflation pressures may get out of hand, leading to a replay of the first half of 2008 when the region grappled with exploding CPI indices. There are already signs that price pressures are returning and policymakers are well advised to maintain vigilance,” the HSBC Global Research team further states. It further predicts inflation to return to most countries in Asia in 2010, noting that price pressures are beginning to resurface.1

Central banks will have the delicate job of pinpointing a suitable time to tighten the reins and dampen the effects of inflation. Just the same, tightening too early has its risk and may slow down growth too rapidly or suddenly, a risk Asian markets can ill afford to take especially when the export sector is far from robust.

“Inflation, deflation and reflation will continue to battle it out in 2010.”

Deflation Makes A Comeback In Japan

In early 2009, in the thick of the global financial crisis, Asia seemed headed for a long drawn deflation. However, a few short months after, Asian markets appear to have steered clear of deflation.

Not so for Japan, though.

Japan has once again, fallen into the gnawing mouth of deflation, an old foe it has battled for over 10 years, in what is now notoriously named “The Lost Decade”. Three years ago, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) declared that it was finally free of the clutches of deflation. Its return must have exasperated policymakers.

Hence, deflation was greeted with a weary hello at the end of 2009, in the form of ¥10 trillion ($115 billion) three-month loans fixed at a 0.1% interest rate. The move was an attempt to boost liquidity and reverse a deflationary spiral. Worth just 2% of GDP, the measure is considered by analysts to be insufficient to reflate the Japanese economy or weaken the yen which on 27 November 2009 soared to its strongest level against the dollar in 14 years.

However, Seiji Shiraishi, Chief Japan Economist for HSBC Securities (Japan) Limited is still positive about Japan, raising an earlier forecast for real GDP growth in 2009 to

-5.7% from -6.3%. He also foresees a GDP growth at 1.2% for 2010, but warns that Japan will continue to be burdened with a negative output gap.

He adds, “Japan will continue to be burdened with a negative output gap, but industrial production and capacity utilisation rates should rise, reflecting increased exports to rapidly growing Asian countries. Manufacturers will probably continue to curtail their personnel costs, so employees’ income will probably continue to decline.”1

Reflation Strategy In Reversing Deflation

In the face of deflation or a slowing economy, policymakers may put into motion reflation strategies. Reflation is the intentional reversal of deflation through a fiscal or monetary policy by central banks and governments. Reflation policies can include increased government spending, lowering interest rate and increasing money supply.

Asian policymakers in the wake of the global financial crisis pumped in massive dollars, with China alone injecting a 4 trillion yuan ($586 billion) stimulus package to its economic veins. But which is winning? Deflation or reflationary measures?

Judging from the surges in the commodity markets and recent positive growth in Asian markets, reflationary forces seems to be gaining the upper hand, which could augur well for us.

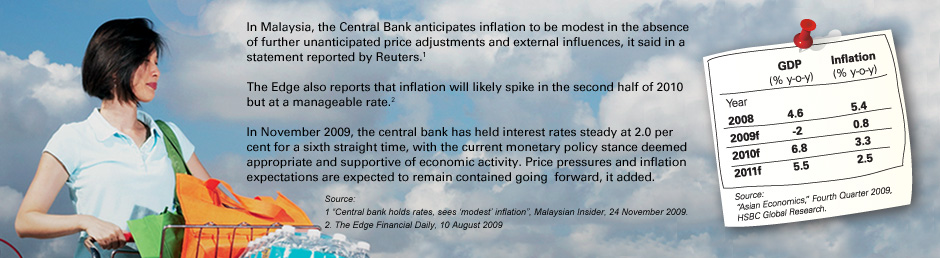

Inflation, deflation and reflation will continue to battle it out in 2010. While the Malaysian economy is currently experiencing modest inflation, we believe that the government’s reflation strategies will continue, though perhaps at a slower pace until exports and the economy picks up traction.

Source:

1 “Asian Economics”, Fourth Quarter 2009, HSBC Global Research.

2 “Inflation or Deflation? Which way is Asia headed” by James Chong, Economic Pulse, Cushman & Wakefield, 27 October 2009.

The Malaysian Pulse: Inflation Is In

Inflation and Deflation 101

What’s The Deal About Inflation?

Inflation as defined by Investopedia.com is “the rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising, and, subsequently, purchasing power is falling. As inflation rises, every dollar will buy a smaller percentage of a good. For example, if the inflation rate is 2%, then a $1 pack of gum will cost $1.02 in a year.”

Inflation is not necessarily a bad thing and a modest inflation often signifies a growing economy. But when inflation goes out of hand, there are repercussions such as:

- Reduced purchasing power. Those with retirement funds or fixed income may find that their savings or income is insufficient to provide for the lifestyle they’ve enjoyed previously.

- Greater uncertainty in investments as it would be difficult to ensure that returns are greater than the inflation rate.

- Domestic products become less competitive globally due to the increased prices.

- In severe cases, hyperinflation can occur. The value of the currency declines so rapidly that it is not worth the paper it is printed on. This may result in the complete breakdown of the economy.

For example, if inflation is 3% a year…

What About Deflation?

Investopedia.com defines “deflation as a general decline in prices, often caused by a reduction in the supply of money or credit.” Deflation increases the purchasing power of the currency, which means a pack of gum today at $1 could cost only $0.80 in a year.

Deflation, with its lower prices, may seem a good thing to consumers but deflation has its hidden dangers. Declining prices, if they persist, generally create a vicious deflationary spiral of negatives which may include the following:

- Delay or reduction in consumer spending causing falling profits for companies.

- Rising unemployment and shrinking incomes as companies close, reduce headcount or cut back on wages.

- Increasing defaults on loans by companies and individuals.

- Economic depression due to a lower level of demand in the economy.

So What Can We Do About Inflation And Deflation

Inflation and deflation are the “yin and yang” of the equation and need to be deftly balanced to aid a country’s economic growth. One way central banks achieve this delicate balance of inflation and deflation is via the adjustment of interest rates.

Source: Charts based on the “Visual guide to inflation and deflation,” mint.com

LIKE THIS ARTICLE?

LIKE THIS ARTICLE?